|

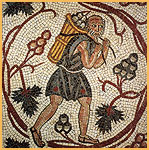

The mosaic decoration

Mosaic, a medium in which small cubes of stone

or glass are set in a  mortar

bed, was a popular way of decorating interiors in Late Antiquity.

Floor mosaics in carpet' formations (a central panel surrounded

by a decorative border) were practically de rigueur during

this period. Floral and animalistic motifs, genre scenes,

architectural settings, and geometric compositions, were the

most common choices in mosaic iconography, both for domestic

and religious use. Specificaly Christian motifs and images

were relatively rare, but this natural world' imagery may

have been used at times with Christian significance to illustrate

the wonders of creation. Topographical mosaics were also popular:

the mosaic of the Yaqto Villa in Antioch (fifth century) shows

the bustling streets of this city and of suburban Daphne;

the sixth-century panel in the church of * in Madaba is a

map of Palestine. Pagan iconography adorns the houses of the

wealthy showing that the ruling classes were fond of antique

culture and perhaps favorable towards paganism, even at a

late date. Narrative scenes, such as Europe abducted by Zeus

or Dionysiac feasts, female allegorical busts, deities and

personnifications adorned reception rooms and sleeping quarters;

often, it is these panels that identify the function of a

particular room and the position of furniture. mortar

bed, was a popular way of decorating interiors in Late Antiquity.

Floor mosaics in carpet' formations (a central panel surrounded

by a decorative border) were practically de rigueur during

this period. Floral and animalistic motifs, genre scenes,

architectural settings, and geometric compositions, were the

most common choices in mosaic iconography, both for domestic

and religious use. Specificaly Christian motifs and images

were relatively rare, but this natural world' imagery may

have been used at times with Christian significance to illustrate

the wonders of creation. Topographical mosaics were also popular:

the mosaic of the Yaqto Villa in Antioch (fifth century) shows

the bustling streets of this city and of suburban Daphne;

the sixth-century panel in the church of * in Madaba is a

map of Palestine. Pagan iconography adorns the houses of the

wealthy showing that the ruling classes were fond of antique

culture and perhaps favorable towards paganism, even at a

late date. Narrative scenes, such as Europe abducted by Zeus

or Dionysiac feasts, female allegorical busts, deities and

personnifications adorned reception rooms and sleeping quarters;

often, it is these panels that identify the function of a

particular room and the position of furniture.

In large prestige buildings tessellated pavements gave

way to marble  slabs,

and monumental mosaics were used to adorn the walls and ceilings.

Religious iconography gained in complexity, with formal images

of holy personnae and extensive narrative cycles. The sanctuary

apse was the

focus for the Early Byzantine church. Early Byzantine apse

themes include divine epiphanies, namely the Ascension or

the Transfiguration, and formal portraits of holy personnae,

such as Christ in Majesty or the Virgin and Child. Apse compositions

also stress the role of the Virgin and patron saint as intercessors

for the salvation of mankind. slabs,

and monumental mosaics were used to adorn the walls and ceilings.

Religious iconography gained in complexity, with formal images

of holy personnae and extensive narrative cycles. The sanctuary

apse was the

focus for the Early Byzantine church. Early Byzantine apse

themes include divine epiphanies, namely the Ascension or

the Transfiguration, and formal portraits of holy personnae,

such as Christ in Majesty or the Virgin and Child. Apse compositions

also stress the role of the Virgin and patron saint as intercessors

for the salvation of mankind.

Often, there is reference to the site, dedication or

patronnage of the church. St Vitale in Ravenna (526-545) features

the Christ, enthroned on a globe and flanked by angels, St

Vitalis and Bishop Ecclesius, the latter carrying a model

of the church; on either side of the apse windows, Justinian,

Theodora and Bishop Maximianus bear gifts to the newly dedicated

church. The Transfiguration on the apse of St Catherine on

Mount Sinai (548-565) is combined with representations of

the local holy man Moses in the

chancel arch, while the face

of the donor Justinian may be recognized in a medallion of

David.

Stylistically, St Vitale and St Catherine illustrate

two different approaches  in

sixth-century mosaic art. In the former monument, solid, naturalistic

figures, set in a real' landscape, derive from classical

tradition. In comparison, the apse mosaic of the Transfiguration

on Mount Sinai, with its large angular figures suspended in

a solid gold background, is almost abstract. The modern approach

illustrated by the Transfiguration mosaic set the trend in

sixth-century Constantinople. The remains of St Sophia's gold

mosaic decoration are entirely non-figural and imitate the

effect of shimmering silks enlivened with geometric patterns.

Prokopios reports

that the church of St Sergius and Bacchus was adorned throughout

with gold, and

Anicia Julian

is said to have gilt the ceiling of St Polyeuktos in order

to prevent her wealth from falling into Justinian's hands,

after the emperor had requested a contribution to the imperial

treasury: both cases may refer to solid gold mosaic. in

sixth-century mosaic art. In the former monument, solid, naturalistic

figures, set in a real' landscape, derive from classical

tradition. In comparison, the apse mosaic of the Transfiguration

on Mount Sinai, with its large angular figures suspended in

a solid gold background, is almost abstract. The modern approach

illustrated by the Transfiguration mosaic set the trend in

sixth-century Constantinople. The remains of St Sophia's gold

mosaic decoration are entirely non-figural and imitate the

effect of shimmering silks enlivened with geometric patterns.

Prokopios reports

that the church of St Sergius and Bacchus was adorned throughout

with gold, and

Anicia Julian

is said to have gilt the ceiling of St Polyeuktos in order

to prevent her wealth from falling into Justinian's hands,

after the emperor had requested a contribution to the imperial

treasury: both cases may refer to solid gold mosaic.

|